Lessons from Corporate Failures: What Really Went Wrong and Why It Matters

- Editor

- 4 hours ago

- 4 min read

by Karnivesh | 19 December, 2025

Corporate failures rarely happen overnight. They unfold quietly, often over years, hidden behind growth headlines, aggressive expansion, or short term performance metrics. When companies collapse, the reasons are usually familiar excessive leverage, weak governance, slow adaptation, and poor execution yet these lessons are repeatedly ignored.

Understanding why companies fail is not about hindsight criticism. It is about recognizing the structural patterns that turn successful businesses into fragile ones.

The Anatomy of a Corporate Failure

Growth without resilience: when scale becomes a liability

One of the most common causes of corporate failure is growth that outpaces financial and operational resilience. Expansion funded by debt can accelerate scale, but it also reduces margin for error.

India’s IL&FS collapse in 2018 is a stark example. With group-level debt exceeding ₹90,000 crore, the company relied heavily on short term borrowing to finance long-gestation infrastructure assets. When refinancing channels tightened, liquidity evaporated. The failure was not about infrastructure demand it was about mismatched cash flows and leverage concentration.

Globally, Lehman Brothers followed a similar path before the 2008 financial crisis. Operating with leverage close to 30 times equity, even a modest decline in asset values was enough to erase capital. Once confidence broke, survival became impossible.

The lesson: Growth amplifies both strengths and weaknesses. Without balance sheet resilience, scale increases fragility.

Governance breakdowns: when trust disappears faster than profits

Financial losses can be repaired. Loss of trust cannot.Repeatedly, corporate failures show that governance weaknesses transform manageable risks into irreversible crises.

Yes Bank’s downfall illustrates this clearly. Between 2016 and 2019, gross NPAs surged from single digits to over 18%, driven by aggressive lending and delayed recognition of stressed assets. By the time corrective action began, capital erosion had already undermined confidence, forcing regulatory intervention.

The Enron collapse remains a global reference point. In 2000, Enron reported revenues of $101 billion, masking deep cash flow weakness through complex off-balance-sheet structures. When transparency failed, over $70 billion in shareholder value was wiped out almost overnight.

The lesson: Governance failures do not create risk they conceal it until markets react suddenly and decisively.

Ignoring disruption: when market leadership creates blind spots

Many failed companies did not miss disruption they underestimated it.

Kodak, once controlling nearly 70% of the global film market, invented the digital camera but delayed its adoption to protect existing profits. By the time digital photography reshaped consumer behavior, the business model had already lost relevance.

Nokia, with almost half the global smartphone market in 2007, failed to transition quickly enough to a software-centric ecosystem. Market share erosion was gradual — collapse was not.

Blockbuster dismissed Netflix when streaming was still niche, overlooking how rapidly consumer preferences could shift once technology enabled convenience at scale.

The lesson: Disruption is rarely sudden. Failure comes from slow strategic response, not lack of awareness.

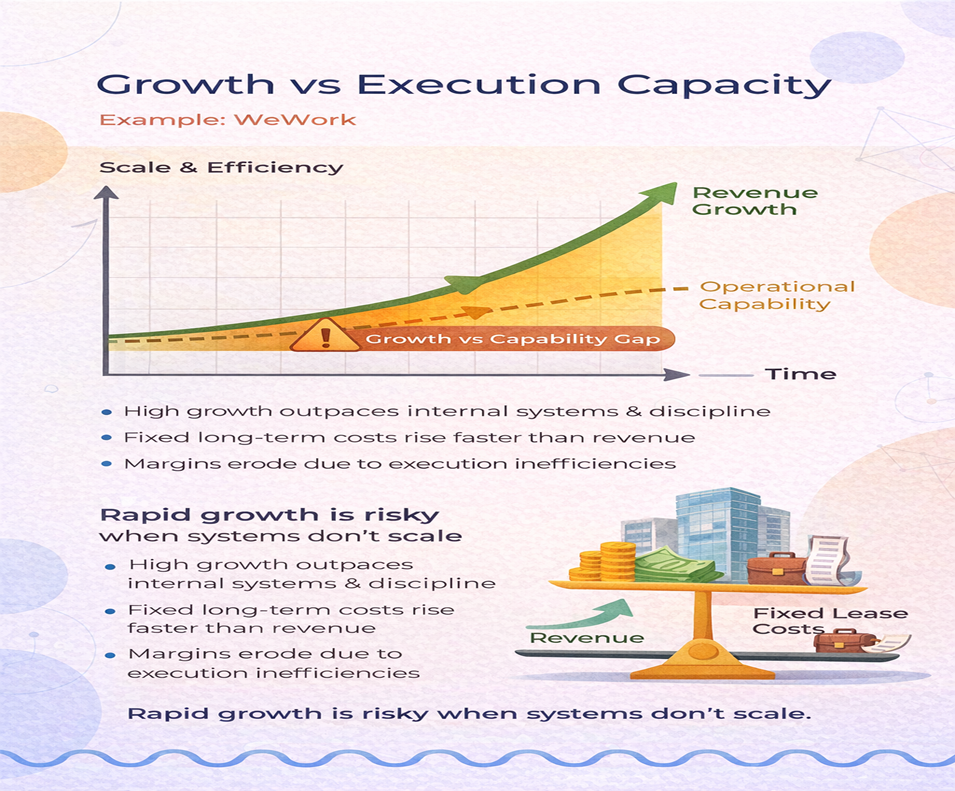

Expansion without execution: when ambition exceeds capability

Rapid expansion often looks impressive in revenue charts but hides operational strain.

WeWork’s rise and reset is a modern example. Despite generating $3.5 billion in revenue in 2019, losses exceeded $3.2 billion, driven by fixed long-term leases funded by short-term, flexible rentals. When market sentiment shifted, valuation collapsed from $47 billion to a fraction of that, exposing weak unit economics and governance gaps.

Similar patterns have appeared in real estate, infrastructure, and retail — businesses that expanded footprint faster than systems, controls, and cash flows could support.

The lesson: Sustainable growth requires operational discipline, not just demand.

Growth vs Execution Capacity

Liquidity decides survival, not reported profitability

A consistent pattern across failures is that many companies were profitable on paper shortly before collapse.

Research published in Harvard Business Review indicates that a majority of bankruptcies are linked to liquidity stress rather than operating losses. When working capital dries up, even strong brands struggle to survive.

Kingfisher Airlines maintained high brand visibility and revenues but failed to meet immediate obligations salaries, fuel payments, and debt servicing ultimately grounding operations.

The lesson: Cash flow sustains businesses; accounting profits do not.

The common warning signs always visible, often ignored

Across geographies and industries, early warning signals tend to appear years before failure:

Debt growing faster than revenue

Declining operating cash flows

Repeated refinancing dependence

Aggressive accounting adjustments

Concentration of decision-making power

These signals are not difficult to identify. The challenge is acknowledging them before momentum masks risk.

Why corporate failures remain relevant today

Studying corporate failures is not about predicting the next collapse. It is about understanding how fragility builds inside organizations often during periods of success.

In an environment shaped by rapid technological change, tighter liquidity, and evolving regulation, resilience matters as much as growth. The companies that endure are not those that avoid mistakes, but those that recognize constraints early and adapt before pressure becomes fatal.

Corporate failures remind us of a simple truth: business success is not permanent, but lessons are if we choose to learn from them.

The collapse is visible. The causes are not.

Comments